![[Francis Naumann]](/4logo.gif)

![[Francis Naumann]](/4logo.gif)

“Kathleen Gilje: Curators, Critic and Connoisseurs of Modern and Contemporary Art,” will open at Francis M. Naumann Fine Art on April 5, 2005.

Kathleen Gilje, who spent years working as a restorer, is today a painter, best known for her skillful reworking of the Old Masters. “Flawlessly executed and slyly doctored,” as one reviewer described them, these paintings “challenge the old boys’ club of traditional art history.”

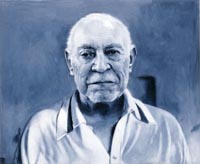

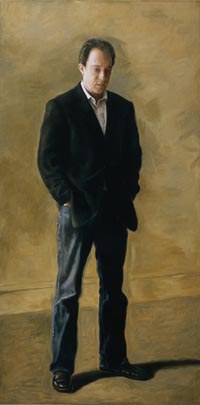

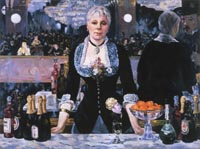

In her new paintings, Gilje has challenged the old boys’ club itself, executing a series of portraits of New York’s best known and highly respected art historians and critics. They are by no means, however, straightforward, convention portraits. Each individual is fused with the identity of his or her historical alter-ego: Robert Rosenblum is rendered at the Count de Pastoret in a painting by Ingres; Linda Nochlin is the barmaid in Manet’s Bar at the Folies Bergère; Arthur Danto is transformed into a marble bust of Socrates; Leo Steinberg occupies the position of Rubens in a memorable Self-Portrait; Michael Kimmelman is the standing, contemplative figure in Eakins’s The Thinker; William Rubin looks like Picasso; RoseLee Goldberg is Manet’s Young Man in the Costume of a Majo; while Charlie Finch is cast as Rembrandt, and Rosalind.

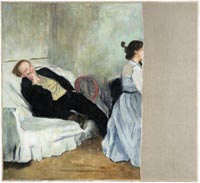

Krauss leans over her typewriter, but looks like she was painted by Degas. Perhaps the most

visually arresting work in the exhibition is the portrait of Lowry Sims, who, with gun in hand, sits majestically on a throne occupying the place of Napoleon in the famous painting by Ingres that hangs in the Invalides in Paris. The most conceptually intriguing is the portrait of Robert Storr and his wife Rosamund Morley who take the place of Manet and his wife in a painting by Degas, a picture that was partially destroyed by Manet, but in Gilje’s ingenious recreation, the missing fragment is magically restored.

Gilje has described the paintings in this series as true collaborations, for in most cases, the art historian or critic provided suggestions as to how they would like to be depicted, some going so far as to pick a specific painting in which they would like to appear. Many posed for Gilje’s camera, in order to assume the same pose as that which appeared in the historical model, while others made photographs available to her.

In his introductory text for the accompanying catalogue, Robert Rosenblum (who, as noted, is the subject of one portrait) describes each of these paintings in detail, and contextualizes the practice of historical portraits from Joshua Reynolds and Vigée-Lebrun, to Cindy Sherman and Yasumasa Morimura. “It’s good to know that in Gilje’s new work,” he concludes, “the same restless ghosts from the pantheon of art history continue to haunt the twenty-first century.”